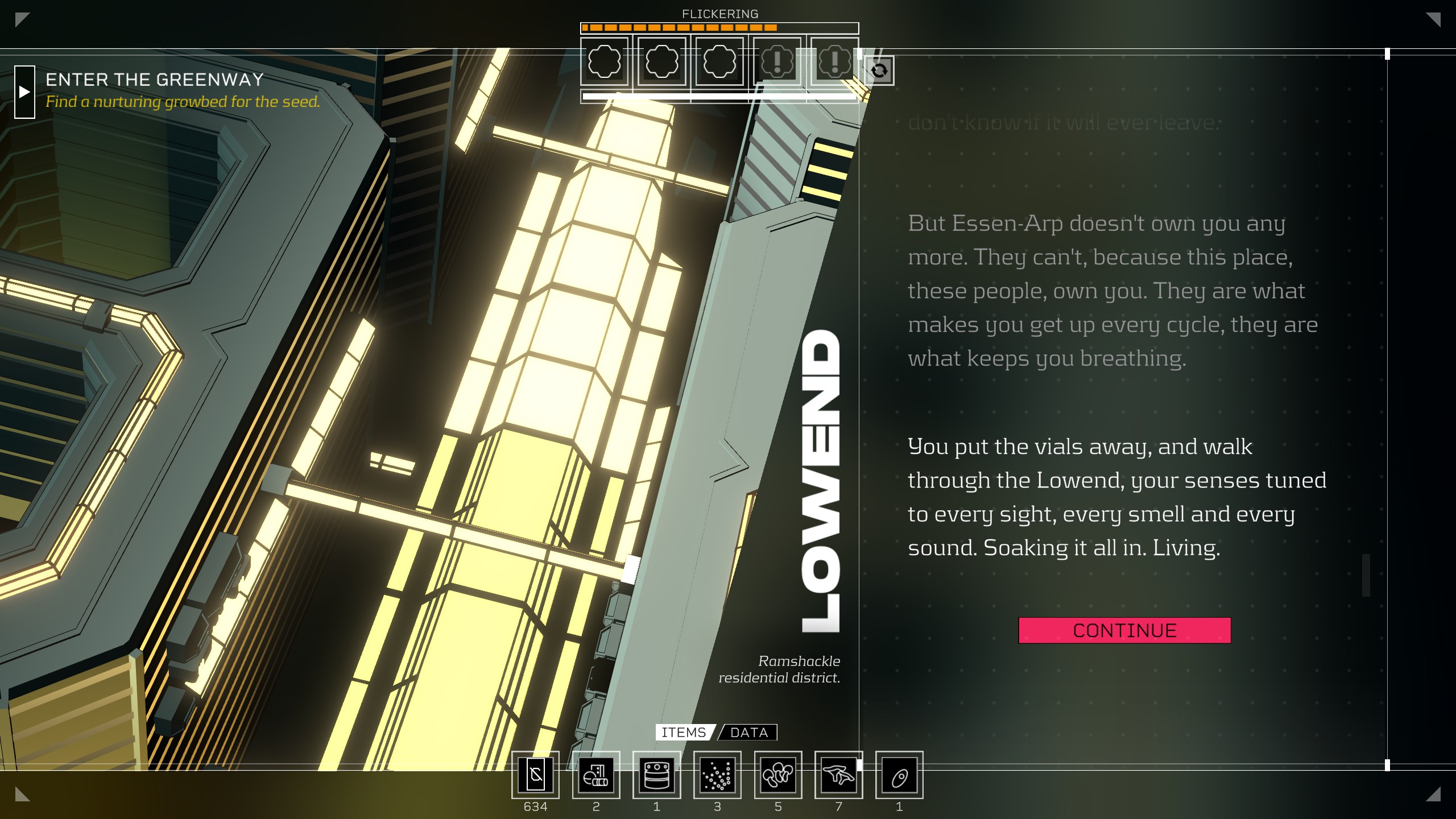

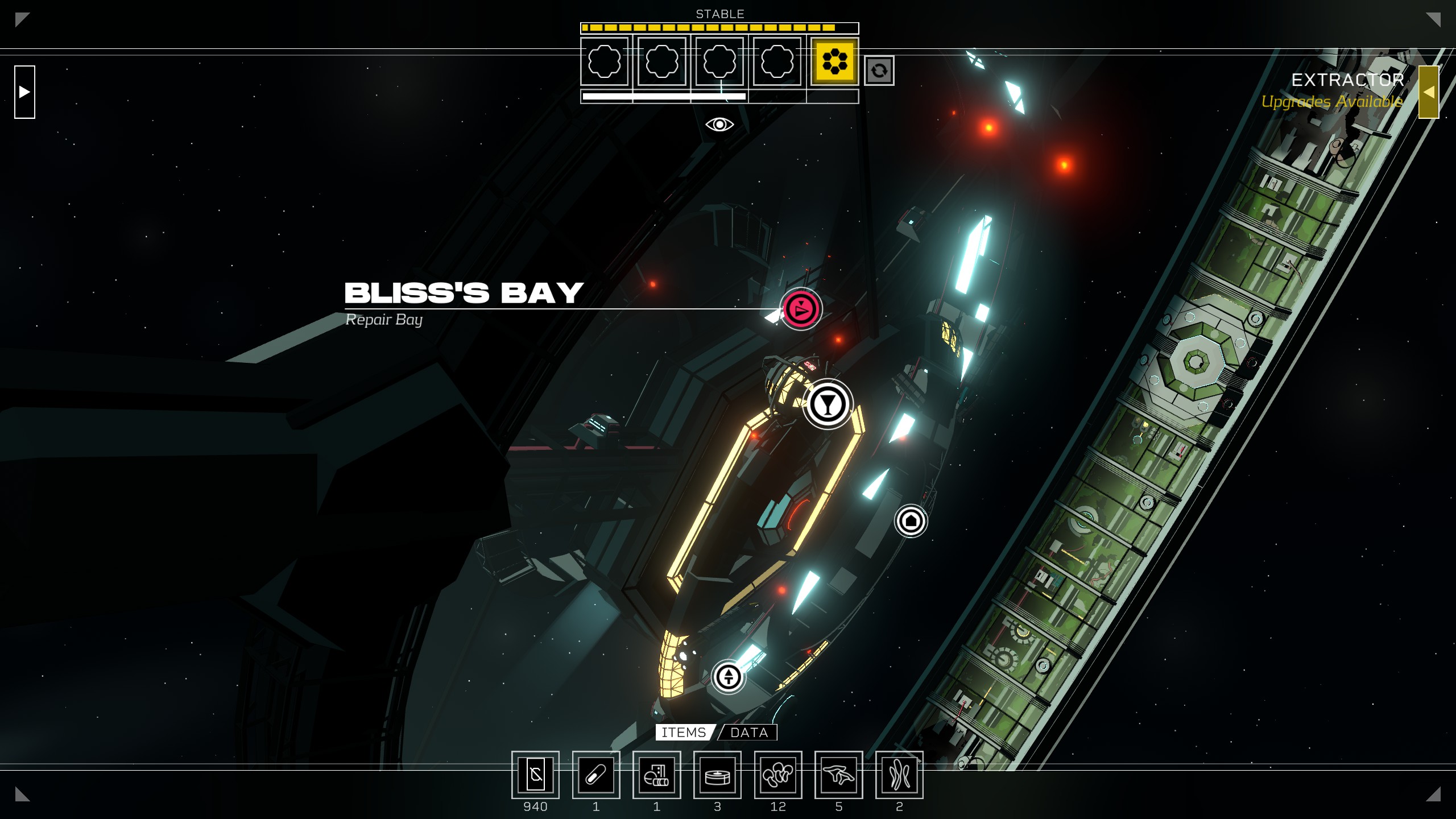

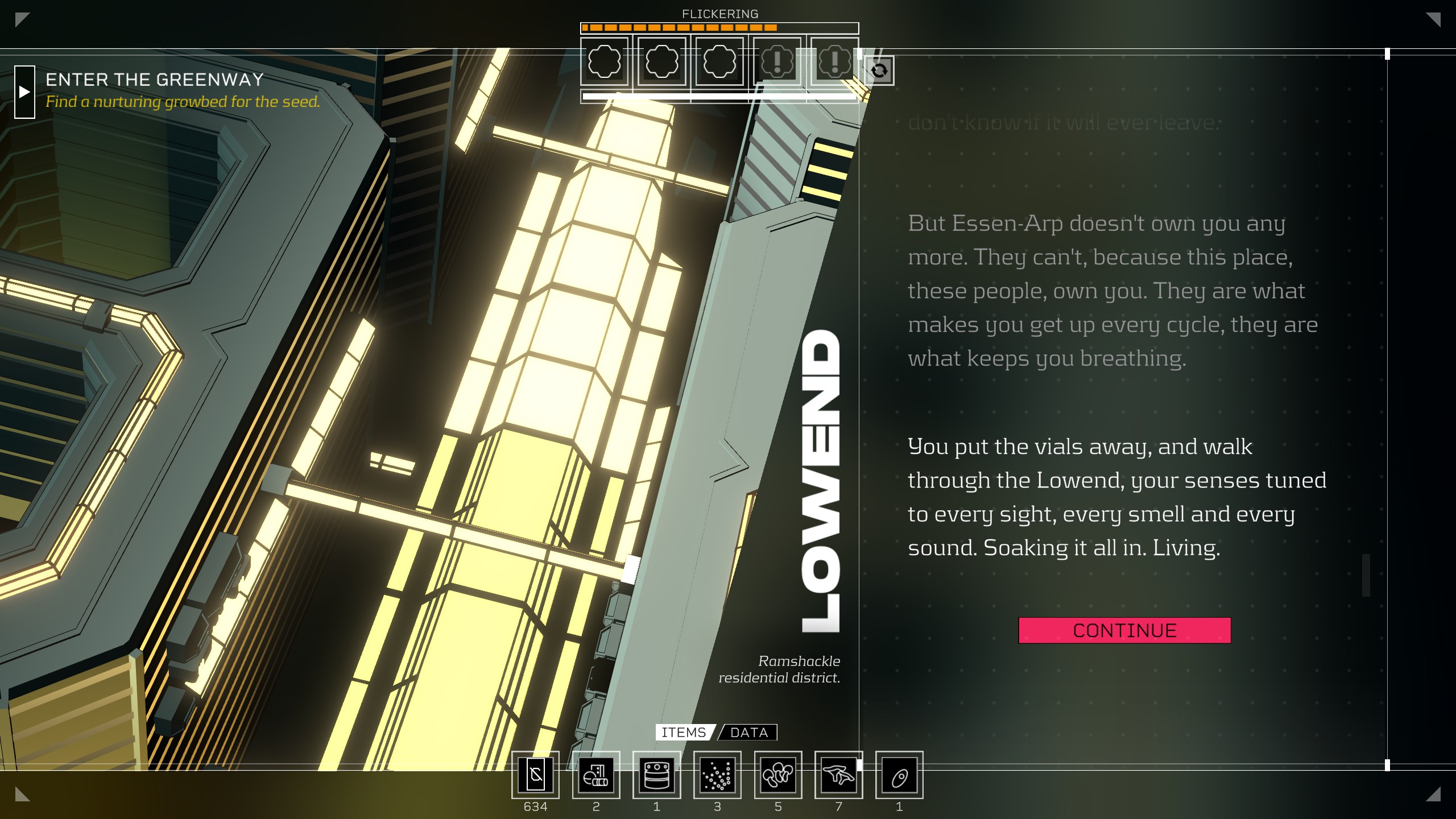

Across the Founder’s Gap — a breach in the otherwise continuous outer ring of the space station called Erlin’s Eye — lies the Greenway, a stretch of the station now overgrown with an abundance of new plant life. Those in the Greenway adhere to a markedly different way of life than those on the opposite side of the gap; the Hypha Commune welcomes those who make the journey into an egalitarian community dedicated to living in harmony with the strange new fauna that surrounds them. Farm stacks, forests full of wild mushrooms, and uncharted wilds define this section of the Eye which, once much like the rest, is now changed.

This all contrasts quite sharply with the way of life your player character, the Sleeper, awakens to at the start of Citizen Sleeper, a new cyberpunk video game by Jump Over The Age. Erlin’s Eye is a station that was once controlled by a company called Solheim, but following a revolutionary movement driven by a man named Andrei Erlin, Solheim withdrew their influence, ceding ground to the new union.

All of this is to say that the culture of the Eye is built amidst the ruins of a capitalist system of social and economic organization — as such, life on the Eye for most of its residents is precarious, but it is especially precarious for you.

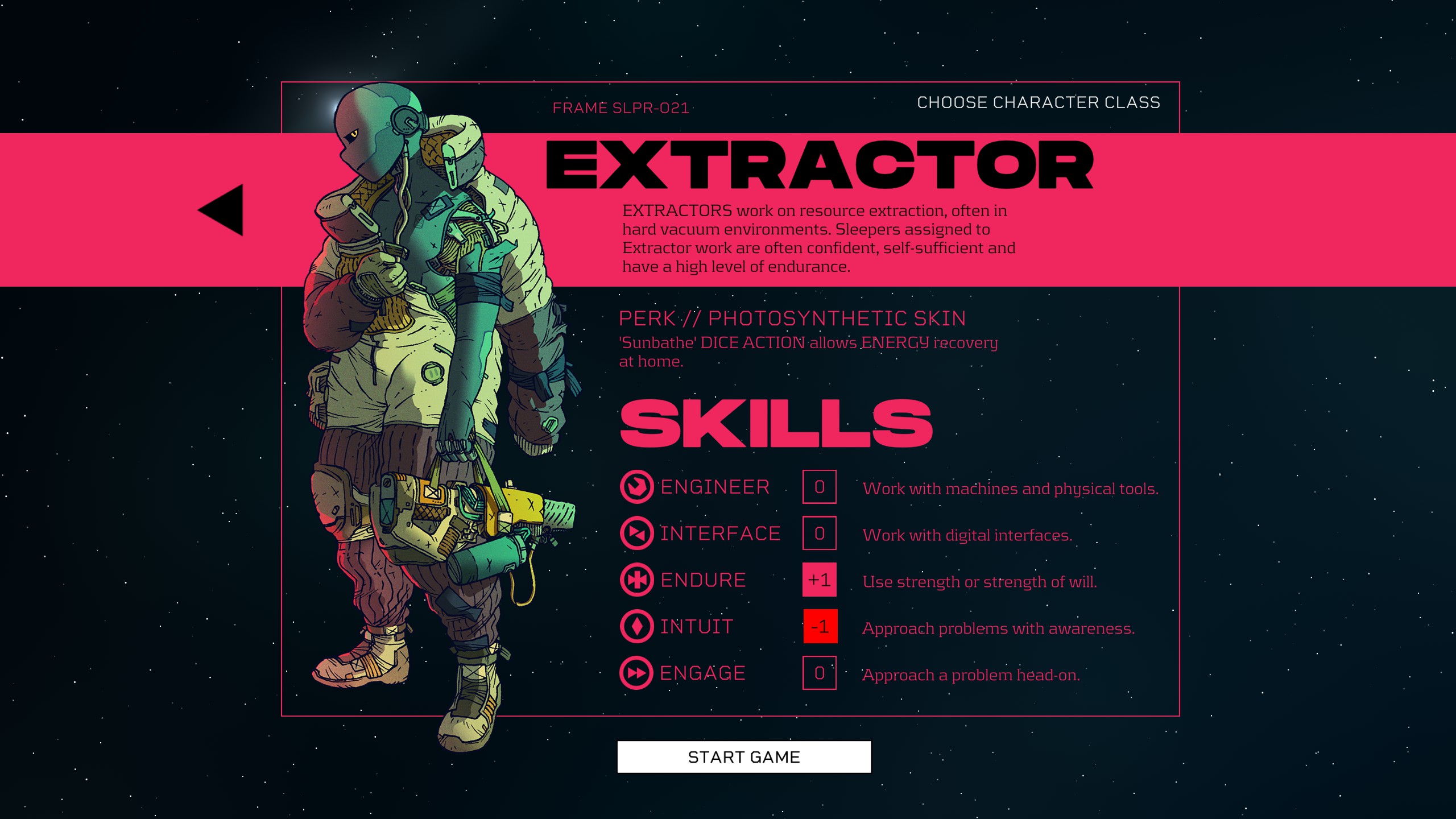

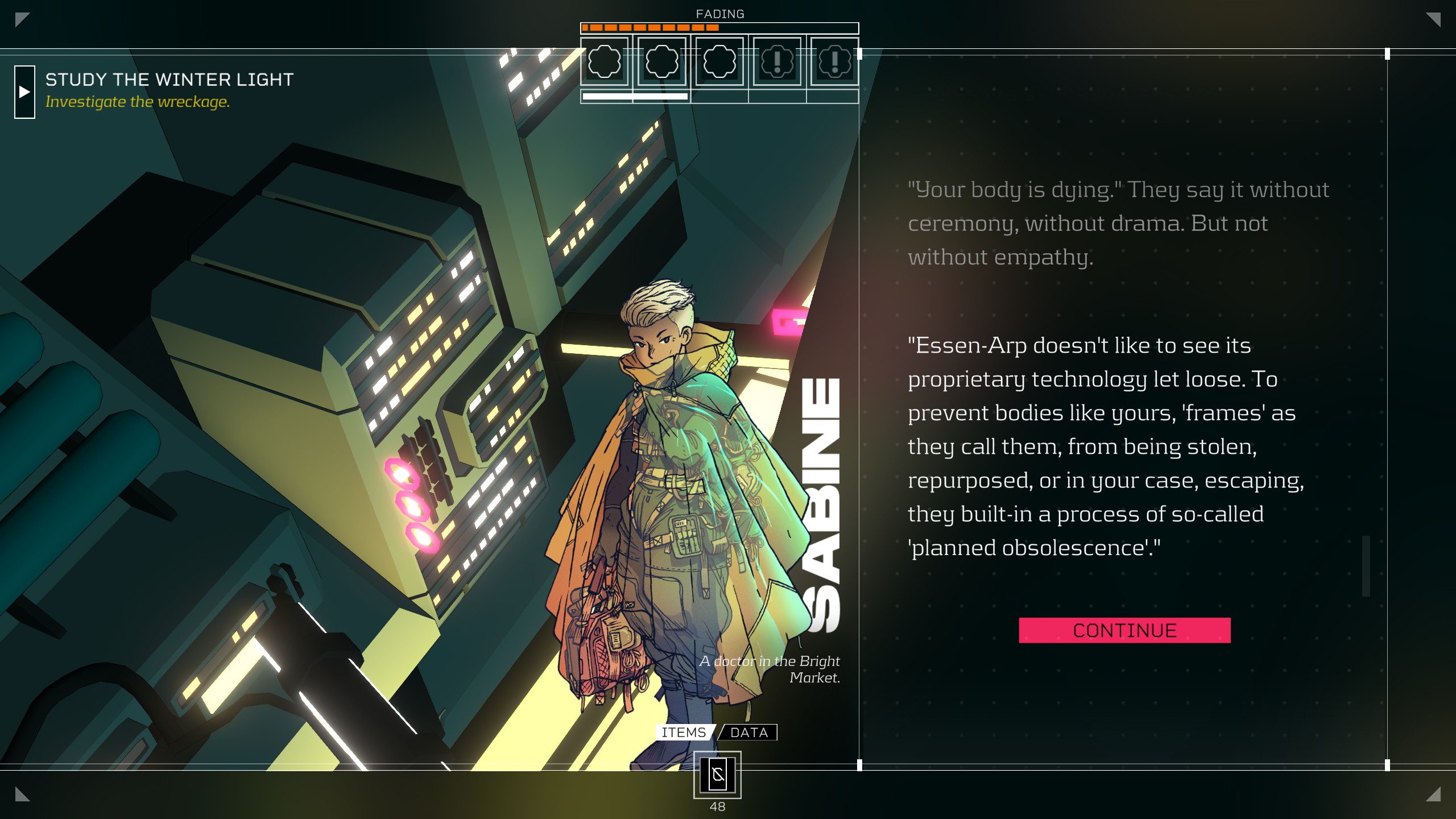

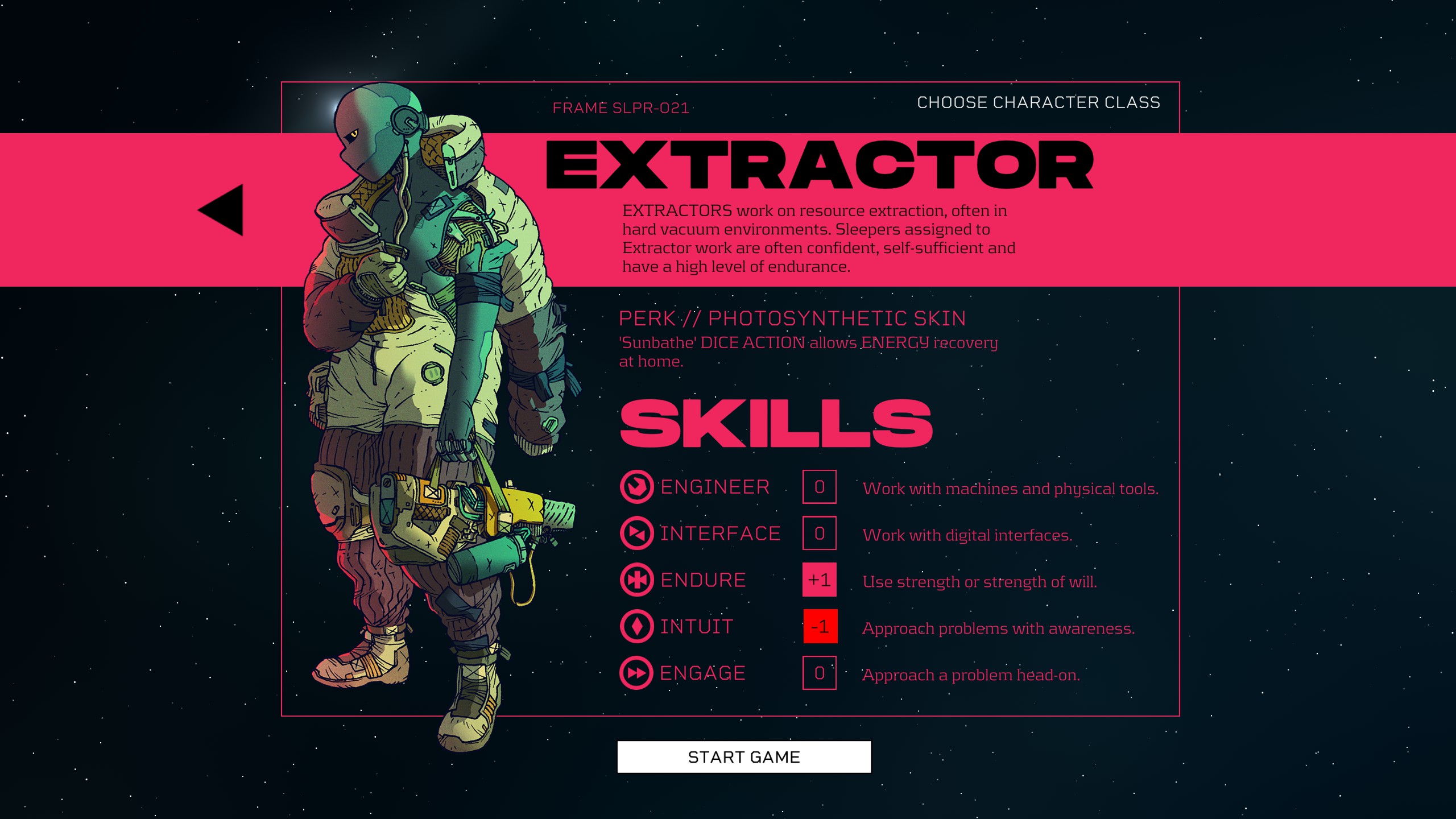

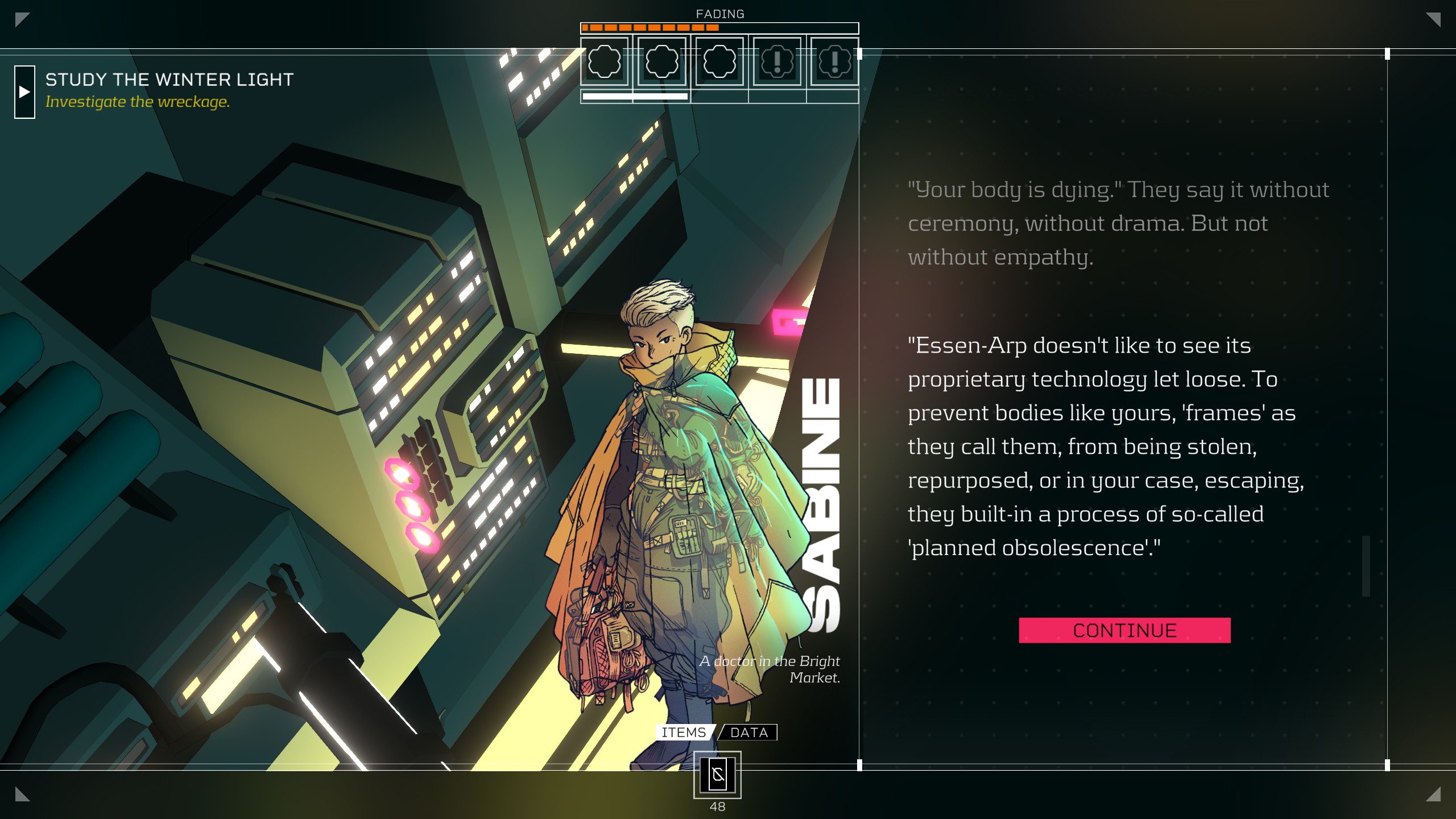

A Sleeper, in the fiction of the game, is an artificial worker, property of a company called Essen-Arp. However, the consciousness governing that body is not artificial — it is the consciousness of a living (or once living) person, somewhere else in the universe, duplicated and transplanted into the body of a humanoid worker drone.

See, as a Sleeper, the artificial body which your consciousness occupies is programmed to succumb to “planned obsolescence” should one escape the life of servitude for which it was manufactured. In the first moments of the game, you wake aboard the Eye, having successfully fled Essen-Arp, and come to terms with your predicament. As a result, you know that the clock is ticking. This means a slow deterioration of your quality of life, your physical capacity, and, in game terms, your Condition.

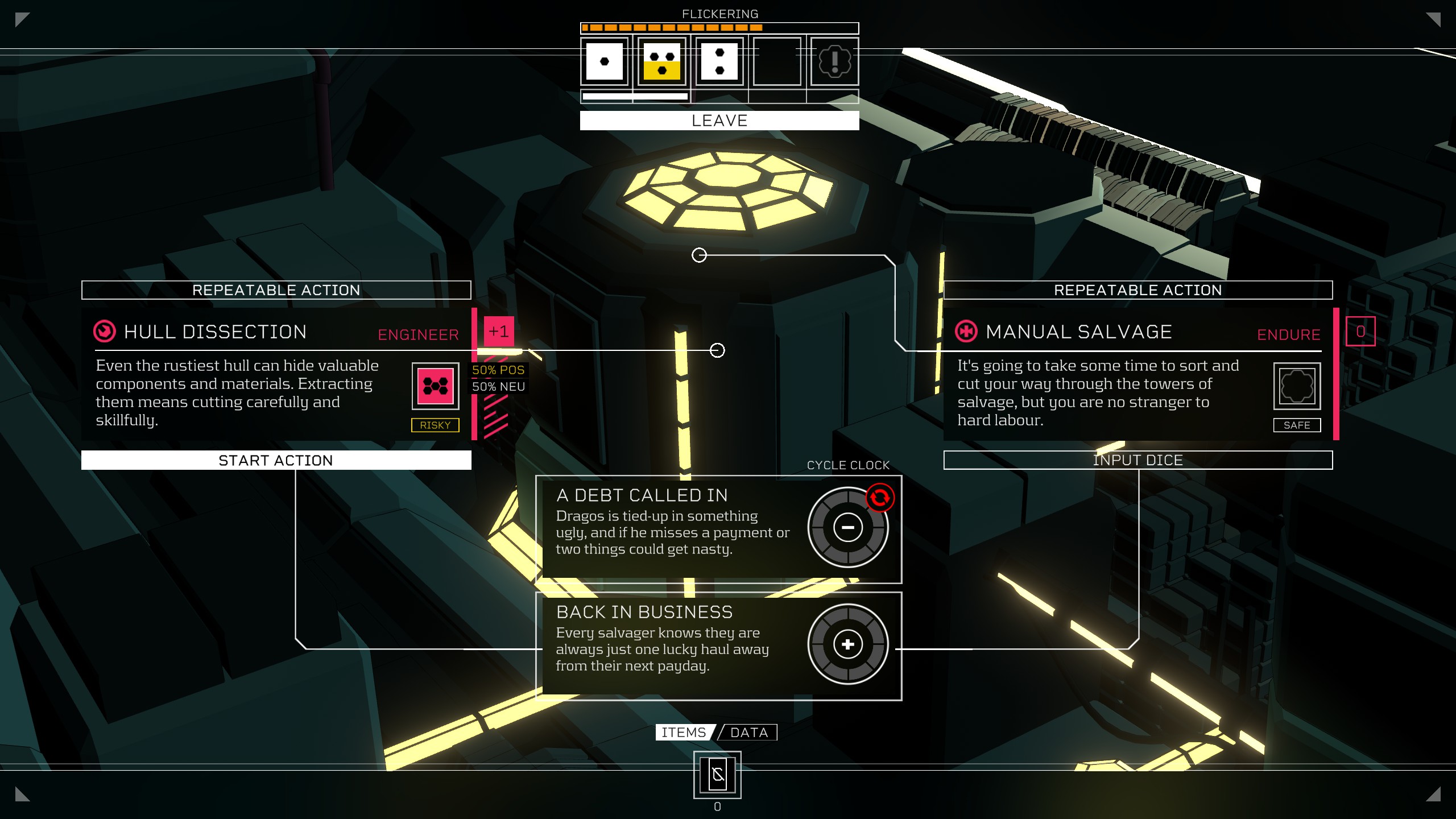

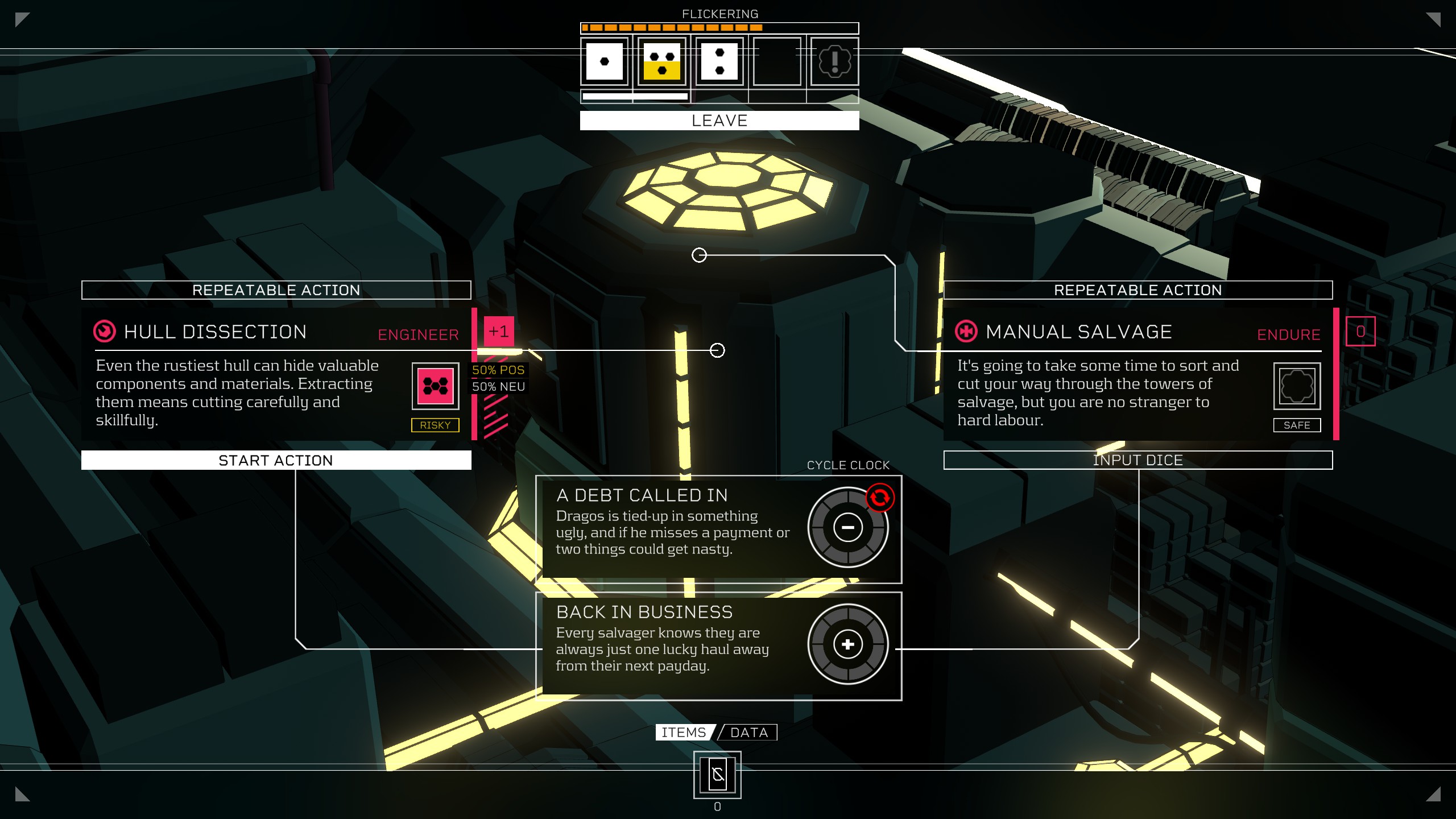

Condition in Citizen Sleeper is a player statistic which governs the number of dice you roll at the start of each cycle, dice which are then used to perform certain Actions at various locations throughout the Eye. Working at the local bar, stripping a ship for spare parts, foraging for mushrooms, or asking around for a doctor capable of stalling the advance of your deterioration — all these actions require the player to spend dice. Actions can also have different costs associated, including cryo (the de facto currency aboard the Eye), hacked data, and various other resources.

As you lose Condition, you roll fewer and fewer dice each cycle, meaning you are able to perform fewer and fewer Actions at a time. It is also effectively your health bar; the game warns that if your Condition reaches 0, you’ll suffer a breakdown. You can lose (or gain) Condition as a consequence of certain Actions, but primarily, your Condition will go down by one point at the end of each cycle.

Alongside this, you also have to keep an eye on your Energy, which doesn’t do much unless you don’t have any; you lose an additional point of Condition if you end a cycle with zero Energy. Just like Condition, Energy can be lost or gained as a result of dice Actions, but the best way to restore it early in the game is by spending cold, hard cryo. Food and drink will restore Energy (Sleepers are much like human beings in this way) where Condition is fully restored by an injected medicine called stabilizer, a rare — and illicit, for escapees like you — treatment that’s all the more expensive as a result.

Thus, the game loop in Citizen Sleeper is: begin the cycle with a new set of dice, decide amongst the available options how to spend those dice, then once they’re exhausted, sleep to replenish your dice and move on to the next cycle. At the start, your cycles will most often revolve around earning cryo and trying to keep your Energy and Condition from bottoming out.

The thing I find particularly compelling about Citizen Sleeper and its game loop is how much room it leaves for the player’s imagination, especially in terms of picturing what happens between Actions and scenes that are explicitly depicted. There is a great deal of suggestion as to what the Sleeper’s life looks like on the Eye, and in situations where I had to eschew progressing character stories in favor of maintaining my physical health, that dilemma did not exist purely in the realm of mechanical or systemic fact but in the fiction as well. The Sleeper intersects the boundaries between all the authored moments and choices, becoming a fully realized person in the process.

Eventually, these mechanical concerns become mostly secondary to the game’s narrative and characters, but it’s crucial that this precarity is established so strongly early on in the game, and by more means than just pure prose. Even when my Sleeper was in a position to do nothing but tend to these two stats, the loop was so compelling, invoking that ‘one-more-turn’ feeling so often used to describe the borderline addictive experience of playing games like Sid Meier’s Civilization, and that loop is something that’s hard to come by in other games with such a strong narrative focus.

NORCO, a narrative-driven game released in 2022 by Geography of Robots, opens with a stunning intro depicting primary character Kay’s circular journey, from her home in Louisiana and back, across an America that is teetering on the precipice of utter chaos. In it, Kay’s experiences in the present mix and mingle with her reflections on her past — memories of her burdensome relationship with her mother Catherine and her brother Blake, which first drove her from Norco, collide with the present feeling of guilt which drives her back. Even the simplest choices in the intro are utterly devastating: do you tell a comforting lie to justify leaving your brother against his wishes, or admit you really don’t even care?

After this intro, the game shifts into its dominant mode as a point-and-click graphic adventure game. You explore the town Kay grew up in, from her childhood home (abandoned in the wake of Catherine’s death to cancer and Blake’s recent disappearance) to bars and creeks and corner stores, clicking on points of interest, talking to local characters, and solving puzzles while searching for your brother.

If I’m honest, the first time I picked up NORCO, I stopped playing after about 15 minutes. It was just enough time to see the intro and first room or two of the house. There were a couple reasons I didn’t pick it up again for a while after that, first among them the fact that I had agreed with some friends to play it as a group (which we’ve now done, which is why I can now write on it more confidently), and I’ve never been much of a point-and-click player myself. Still, it struck me how quickly I was prepared to put the game down, especially after such a strong start.

In the end, I attribute it to the game loop; beyond the quality of the prose and the world, the loop doesn’t do much on its own to captivate and compel you to keep playing. I bring it up here as a contrast to Citizen Sleeper because, when I played Citizen Sleeper just a few weeks after bouncing off NORCO, it got its hooks in me deep.

. . .

The other mechanisms that augment Citizen Sleeper’s core game loop are Clocks and Drives. Clocks are elements of the user interface that represent various fictional circumstances — they fill with a predetermined number of Ticks, and then, once filled, have some effect. One example is a major factor of your early experience in Citizen Sleeper: a Clock, called Hunted, which represents the threat posed by your still-active Essen-Arp tracker. It ticks each time you end the day, and the implicit threat of what might happen when it fills pushes you towards particular characters and tasks.

The game helps you track these various plot threads and goals with what are called Drives, which act as the game’s objectives. Drives exist to help the player keep track of various plot threads and goals, including isolated tasks (constructing a Shipmind from three cores, growing mushrooms), character requests (integrating that Shipmind with a newly repaired ship, renovating a bar), and your player character’s overarching concerns (disabling that tracker which will eventually lead an Essen-Arp assassin straight to your door). Drives are pre-authored, pointing the player towards what will help them progress in the game, and then offering upgrade points when the Drive is accomplished.

Both of these ideas, Clocks and Drives, are adapted with varying degrees of directness from games like The Sprawl and Beam Saber, tabletop role-playing games with strong focuses on narrative over crunchy stats and tactical gameplay. These games themselves are in fact “hacks” of other pre-existing tabletop RPGs: The Sprawl is derived from the rules and systems of a game called Apocalypse World, and Beam Saber is similarly built off the bones of Blades in the Dark. Hacks of these games are common enough to have their own monikers — Powered by the Apocalypse, Forged in the Dark.

Games in this lineage follow a popular principle that emerged in independent tabletop games in the early 00’s called Fiction-First, which places value on players foregrounding a tabletop game’s fictional situation over the mechanical situation; players initiate their turn not by saying “I want to roll Maneuver” but instead by describing the fictional action, then deciding as a table whether Maneuver is appropriate as opposed to Bombard or what-have-you. Fiction comes first; mechanics follow.

The developers of Citizen Sleeper cite tabletop games as a key influence openly and repeatedly — on the game’s website, in interviews, in conference talks. It’s also quite clear which games in particular had the most influence; aside from the clear mechanical connections above, Gareth Damian Martin — the one behind the Jump Over The Age moniker, and lead developer on the game — said in a fireside chat with Austin Walker, host and GM of the tabletop Actual Play podcast Friends at the Table, that the games highlighted on his podcast were critical in the development of Citizen Sleeper (The Sprawl was the played in the second half of Friends at the Table’s cyberpunk-mecha season COUNTER/Weight, and in its distant-future sequel PARTIZAN, Beam Saber was the primary game).

Of course, there have been countless video games influenced by tabletop RPGs, but what we see most often are games using d20 systems like D&D, primarily modeling its turn-based combat and emphasis on acquiring more and more loot. Like the Fiction-First games of the indie tabletop renaissance, Citizen Sleeper forges a new path, reevaluating the systems it employs and placing full emphasis on things not commonly found in other digital RPGs.

. . .

(I didn’t remark on it above, but I must do so here: Friends at the Table is my favorite podcast, and has been for years. I consider it a personal duty to recommend it to anyone who I think may find as much joy in it as I do. So: please listen to Friends at the Table. Okay, back to it.)

. . .

Despite the sheer number of digital games influenced by tabletop RPGs, almost none accurately capture the magical quality that makes tabletop play so profound and compelling: the radical potential of a story yet told. There is no script, no golden path, no single linear narrative, no boundary so total it cannot be circumvented. When players take a seat at the table, they do so in large part to actualize that potential into something real — a story that belongs to them.

Of course, if you know anything about digital game development, you are aware that this quality cannot be sufficiently replicated in digital games. Scope is a constant consideration and not one easily overcome. Many have tried, and put various methods to the task — procedural generation, branching narrative design, and the sheer power of a massive budget to name a few — but all these methods have costs and drawbacks, and none can disguise the truth for terribly long; to make a digital game, you must, at some point, define its boundaries. Citizen Sleeper is no exception.

This is not, to be clear, a failure of the medium; it’s a constraint, one which begs developers to approach things in creative ways. The result is countless design innovations, including those listed above, as well as games which simply accept this limitation of scope and make the most of what they can.

Citizen Sleeper is an extremely scope-conscious game, one made by an incredibly small team, and I think the tabletop connections I’ve laid out above help explain how it works so magnificently within that scope. Beyond that, I think the game presents a vision for how other small developers can do the same.

So, to recap: in Citizen Sleeper you have Drives pointing you towards meaningful activity, Clocks reminding you why you should pursue said activity, dice with which to perform Actions, and stats like Energy and Condition to keep topped off at risk of harm. Filling certain Clocks or taking certain Actions will trigger authored narrative moments, where the player is presented dialogue and inner monologue in text form. All of this, each element — the Actions, the Clocks, the Drives, the prose, the Eye — was created by hand, but it’s harder to isolate responsibility for the spaces between them in the same way. Players move between the different pieces in different ways, and suddenly what one player experiences without struggle becomes an agonizing choice for another. The player’s affective relationship with the game and its world, the characters they care about, the things they choose to do to make money, to kill time, to recover energy, all of these combine in a way that is complex and hard to predict, though of course certain patterns emerge, at least in my anecdotal experience.

What is remarkable is that Citizen Sleeper is decidedly a narrative-driven game, but I would say half or less of my time with it was spent reading prose; more importantly, the game loop itself is charged by the prose rather than hampered by it, and vice versa. Characters in the game speak of precarity, economic and otherwise, and those words don’t bear the sole burden of communicating and selling this state of being to the player — all the systems of the game combine to reinforce it.

(This feels like the time to also highlight just how strong the prose in this game actually is. It’s not perfectly even throughout, and it’s impossible not to notice a number of typos and grammatical errors, but for a game with nothing but text and static character portraits to be able to depict, for example, a convincing and tense fight/chase scene is quite impressive, at least to me!)

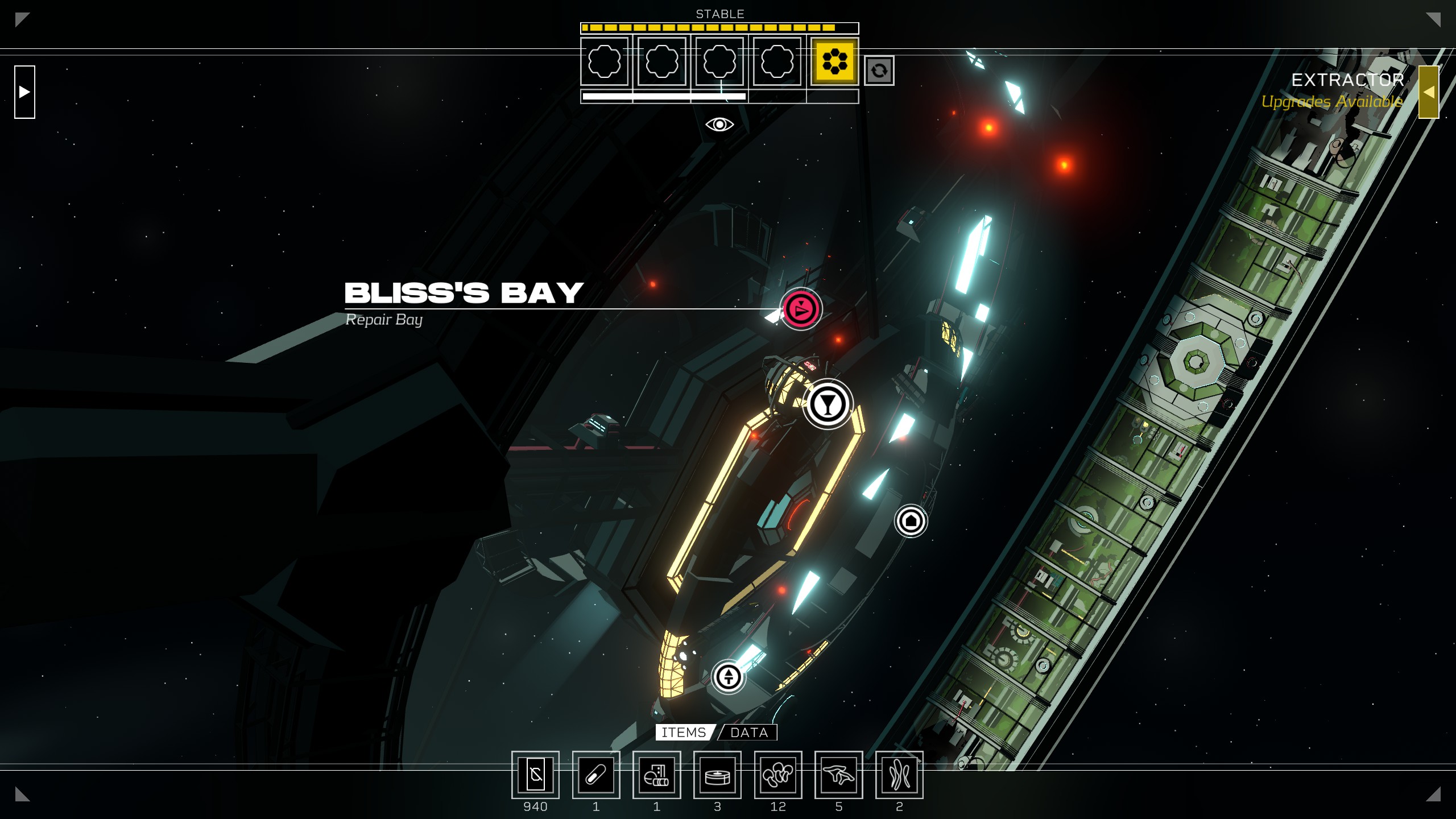

All of this is related to the idea of game systems as generative of narrative, which is core to how many tabletop RPGs operate. Citizen Sleeper strikes such a tremendous balance between authored content and systems, and at the same time it gives the player the space to play with your Sleeper’s characterization in those gaps. For me, getting my hands on cryo was often not as simple as going for the highest payout (that was the tavla tables in the gambling parlor, at least it was until a recent patch); I would go work a shift in the Overlook bar if it felt like it had been too long since I’d seen Tala, or, if it happened to be a busy cycle for Bliss and her repair shop, I’d go up to the Hub and work like hell, sleeping in a nearby capsule to skip the commute. Sometimes the active Clocks would ring so loudly in my ears, the threats or pressures they symbolized so vivid, that it would make the choice for me. The narrative just has a way of infecting you and coloring all of your choices — not just in dialogue but on the game layer as well — and by making those choices with all that in mind, you color the narrative right back.

. . .

I feel very strongly about each and every character in Citizen Sleeper’s cast. That’s not to say I love all of them, though it’s not far from the truth. Characters and their personal stories are the core of this game’s narrative structure, and I’m eager to talk about some of them, so if you don’t want any spoilers at all, skip this section; I won’t be too explicit to start, but I eventually discuss the game’s ending(s), and their narrative design, in some detail.

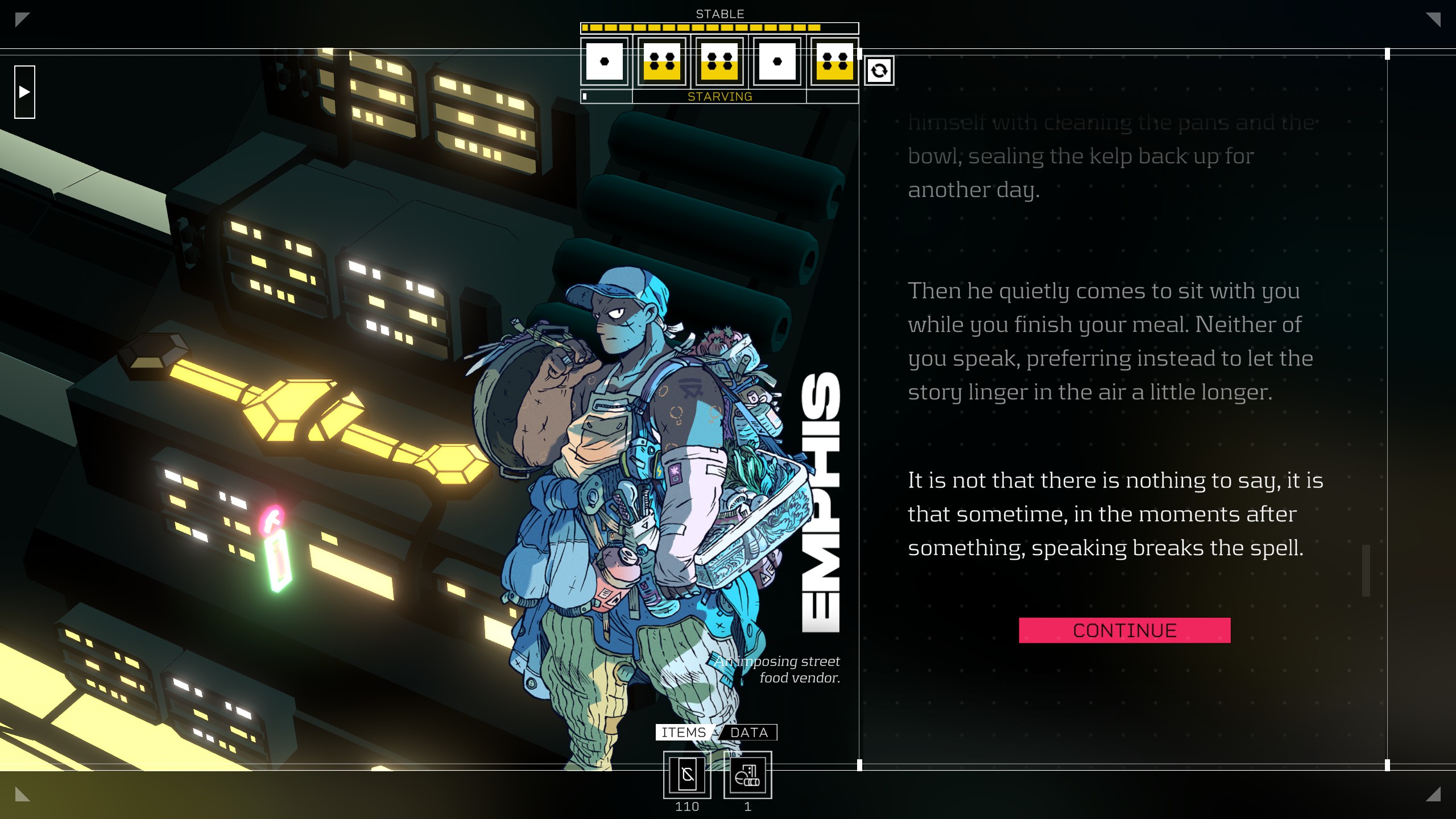

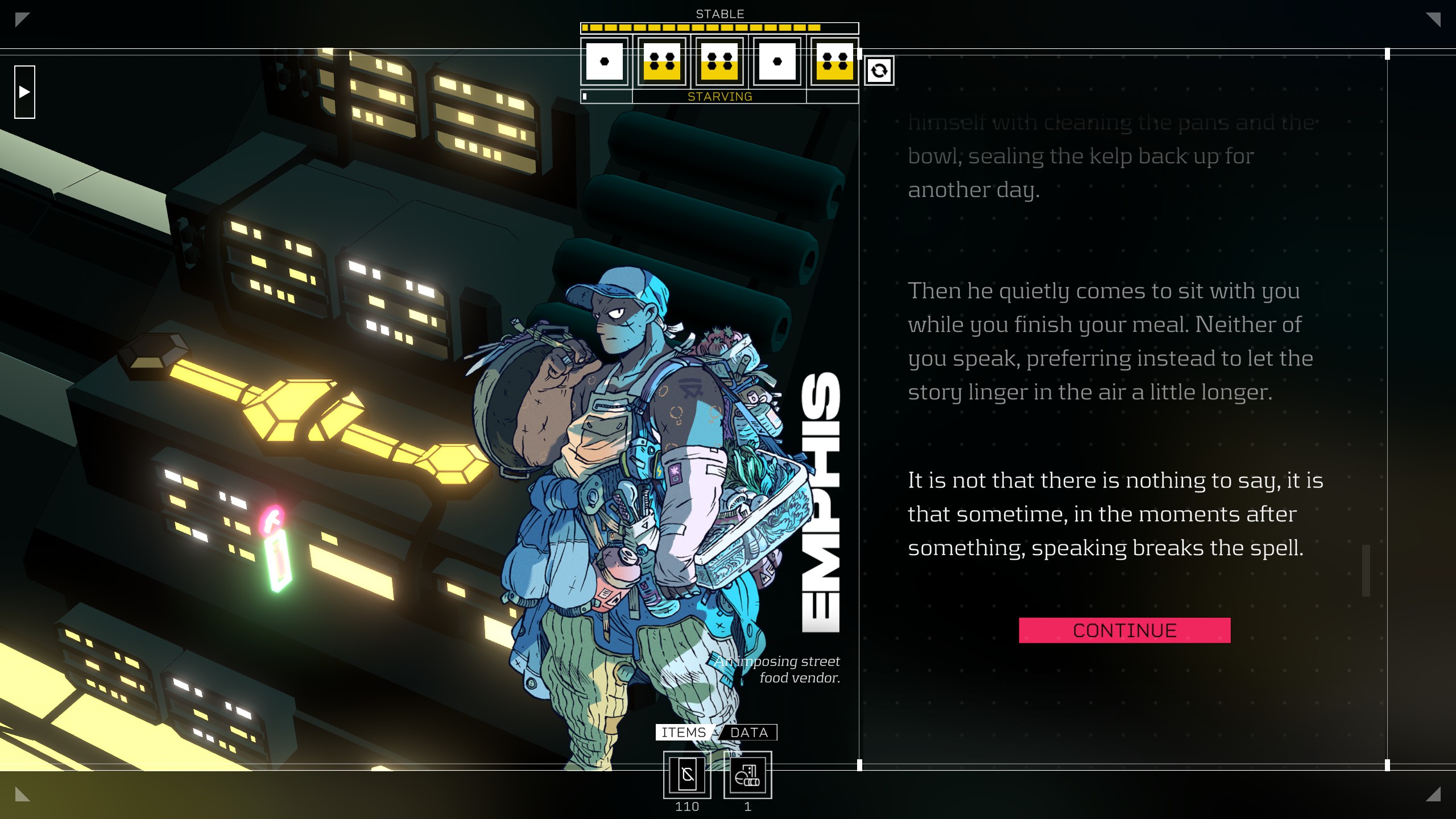

The first character I was struck by in the game is a chef named Emphis. He runs a food stand selling cooked fungus near the Lowend, a large housing complex that’s effectively run by a criminal organization called Yatagan. You can meet him very early in the game, and he quickly reveals that his favorite thing about being a chef is getting to hear stories shared over a meal. He promises to share his with you if you can acquire some rare mushrooms for him; he rarely has time to leave the stall and you seem just the type to find what he’s looking for. That’s a new Drive: get mushrooms for Emphis.

This Drive, from the time I logged it to the time I finally fulfilled it, spanned at least half of my playtime with the game. It’s one of the least urgent tasks you’ll be assigned in the game but because I instantly felt an affection for Emphis, it was always on my mind. Everywhere I went, I thought maybe I’d stumble on a cluster of mushrooms to bring back for him. Emphis’ fungus has incredible bang-for-buck when it comes to restoring your Energy, so I frequented his stall and could easily imagine my Sleeper’s head buried in the bowl, apologizing once again for having not found what Emphis was looking for.

The other instance of instant affection for me was not one character but a pair. Lem, a single working father you meet on a job constructing a massive spaceship, and Mina, his very young, very shy adopted daughter, exist to tug on your heartstrings, and at least in my case, they did so effortlessly. There is a tenderness and warmth to all of the writing in the game, but the scenes with Lem and Mina in particular are just heartbreaking in how they depict the precarity these two face, and in their attempts to relate to the Sleeper in that respect. Their story goes in directions you will probably see coming, but the nuances to the consequences of your choices in regards to their fate are really compelling.

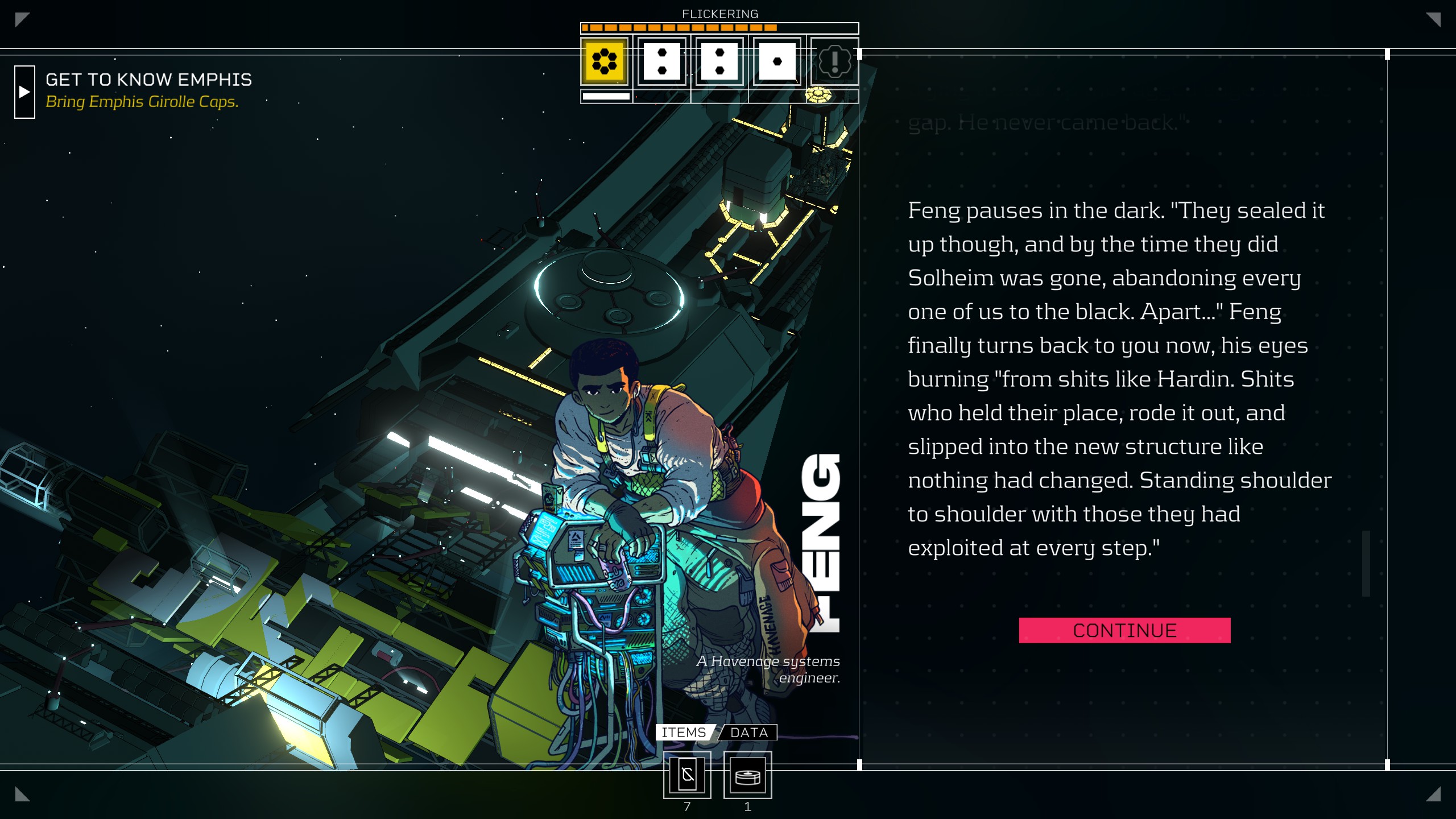

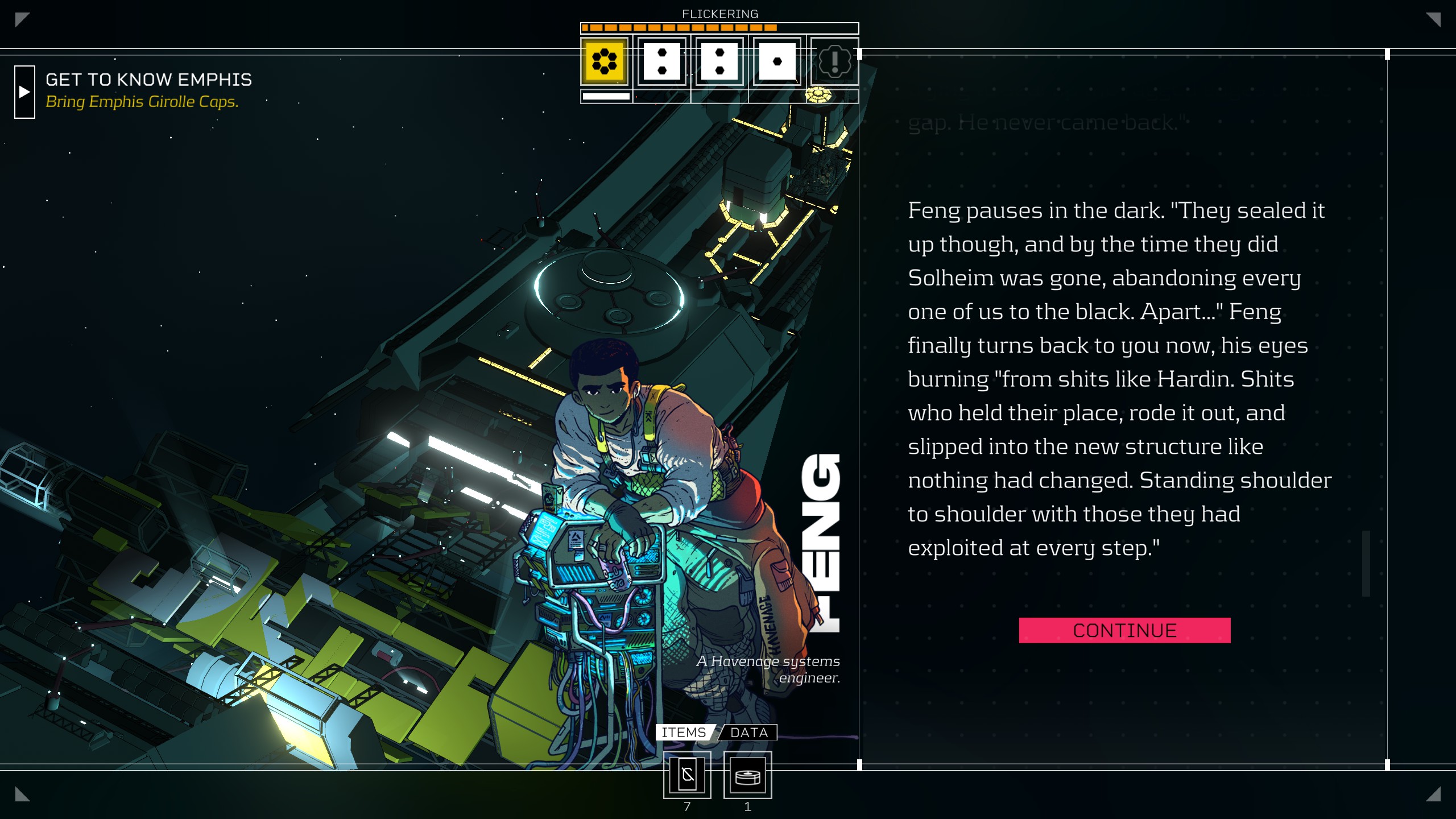

Oftentimes, you can tell with some certainty how the creators wanted you to feel about various characters in this game, but I think there’s an interesting gulf between those authorial intentions (or at least expectations) and with a character named Feng, at least in my experience with him. Feng is another character you meet very early in the game, and he immediately strikes a very important bargain with you: he offers to disable the tracker embedded in your body — the same tracker those Essen-Arp assassins are almost assuredly using to find and kill you, as suggested by the ever-present Hunted Clock — in exchange for your help digging into some mysteries aboard the Eye.

Feng is a compelling character, don’t get me wrong. He has conviction, he has a sense of humor, and his portrait perfectly sells his affable attitude. His quest for answers and, inevitably, justice is a major element of the game for more than half its playtime, so much so that it starts to feel like the central plot in Citizen Sleeper. In the fireside chat linked above, Damian Martin names Feng as one of their favorite characters in the game’s cast, and it’s not hard to see why.

But an interesting thing happens when you compare Feng, the character as he exists in the prose, with the Feng that exists when that prose is synthesized with the game’s systems and design. Your reason as the Sleeper for working with Feng is almost solely to shake your Essen-Arp pursuers, who loom like reapers over the narrative and present an existential threat to your playable character. The Hunted Clock begins with a small number of ticks and fills up each time you end a cycle, something you do with alarming frequency in the first hour or two of Citizen Sleeper. It’s not hard to complete Feng’s initial request, but as he keeps talking in the dialogue following your success, it becomes clear he’s not going to fulfill his end of the bargain anytime soon. Ultimately, Feng is a person who strings you along on a life-or-death issue to settle a political score that you may or may not have any interest in. The design of the game tells you that he doesn’t give a fuck about whether you get got or not, and it was very hard for me to square that with how he’s presented in prose.

Frankly, the complexity of emotion evoked by this character and his quest is completely fascinating to me. The presence of the Hunted Clock (which persists as a threat longer, and in stranger ways, than you might imagine) is really, to me, the thing that gives the game systems weight. Everything else you do sits in contrast with this predicament — spending time working up the money for stabilizer feels like solving a short-term problem as you ignore the long-term problem creeping up on you.

From an authorial perspective, it makes perfect sense to keep this noose about the player’s neck for as long as it feels narratively plausible. The tension the game has maintained for hours deflates significantly once this storyline resolves, because by that point you’ve probably established a pretty safe method for acquiring the things you need to keep Condition and Energy topped off. You still need them in order to survive, but the prioritization between long- and short-term threats no longer influences your decision-making in the really juicy ways it did before. But the decision to tie this weighty Clock to a character like Feng inadvertently makes him feel more manipulative than he comes across in dialogue.

Brief aside: it’s hard to tell when you begin Citizen Sleeper how seriously the game is going to treat death, and in particular, whether it employs a roguelike structure; you, like me, might ask yourself, “Am I meant to die in this game? If I do, will I have to start it all over again?” It’s all dice and Clocks and survival, after all. These questions of genre and convention are inextricably tied up with the Hunted Clock — if the threat ever manifests (you suppose), you will find out very quickly just how seriously the game treats death.

If you’ve made it this far in the piece, you probably won’t mind me being clear about this: Citizen Sleeper is not a roguelike; in my experience and the experience of others I’ve spoken with about the game, I believe it is impossible to die and you most likely will not have to replay significant chunks of the game. What I want to communicate, then, is simply that these questions amplify the resonance of the design elements the game employs, and charges the Hunted Clock with incredible power.

. . .

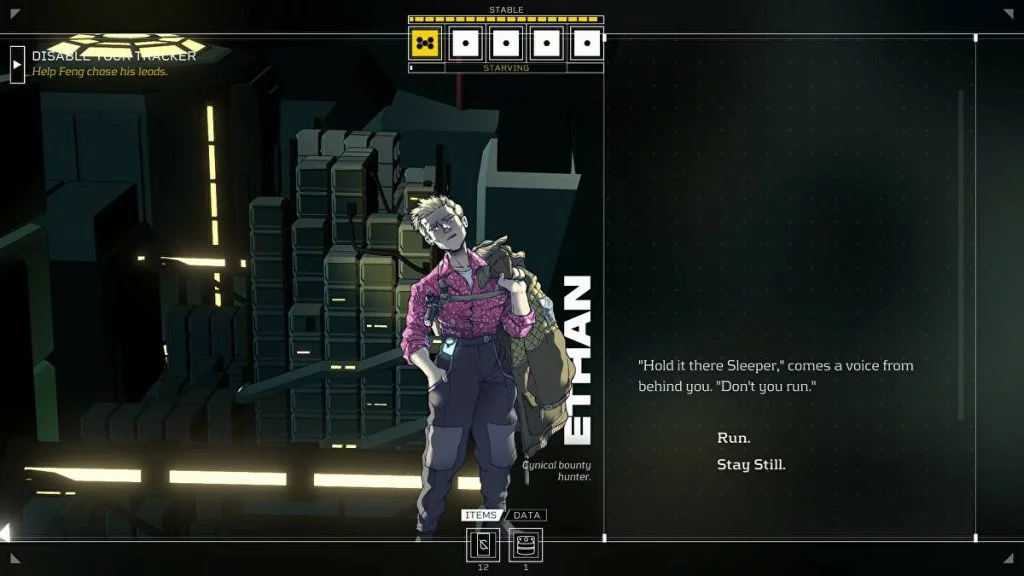

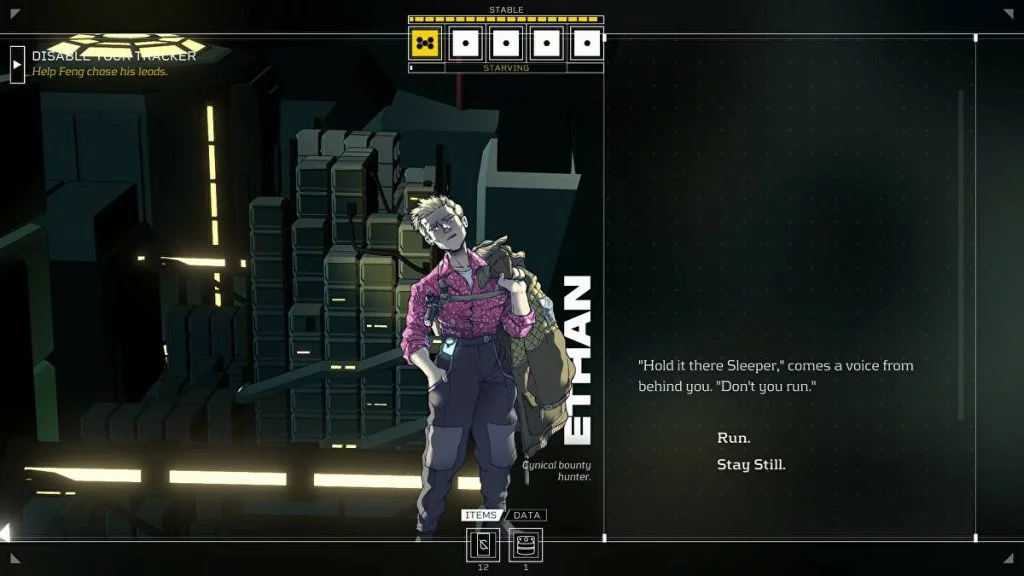

Luckily, just after you realize Feng has fucked you over, you get introduced to an all-time piece of shit who elevates this plot thread from good to electric. Ethan, the bounty hunter sent to capture and/or kill you, hates his job just as much as everybody else on this station. He doesn’t wanna bag you because to do so would end the semi-lucrative ongoing payments he receives as long as the contract is out. So, in a tense first meeting, he decides to push his luck and try to coerce you to earn cryo in order to fund his bad habits. You soon learn he does this with most Sleepers he’s sent after.

What can be said about Ethan? He’s incredible. I was in absolute delight throughout his entire introduction — bug-eyed, laughing nervously, the dumbest smile across my face. At the same time as the game seems to pull a punch with regard to the Hunted threat, it introduces a character whose volatility and violent potential is clear from the jump. With Ethan on board the Eye, your safety is no longer an abstract concern represented by something so simple as a Clock — at any moment, it feels like Ethan could show up and ruin your fucking life.

More explicit spoilers follow. You’ve been warned.

. . .

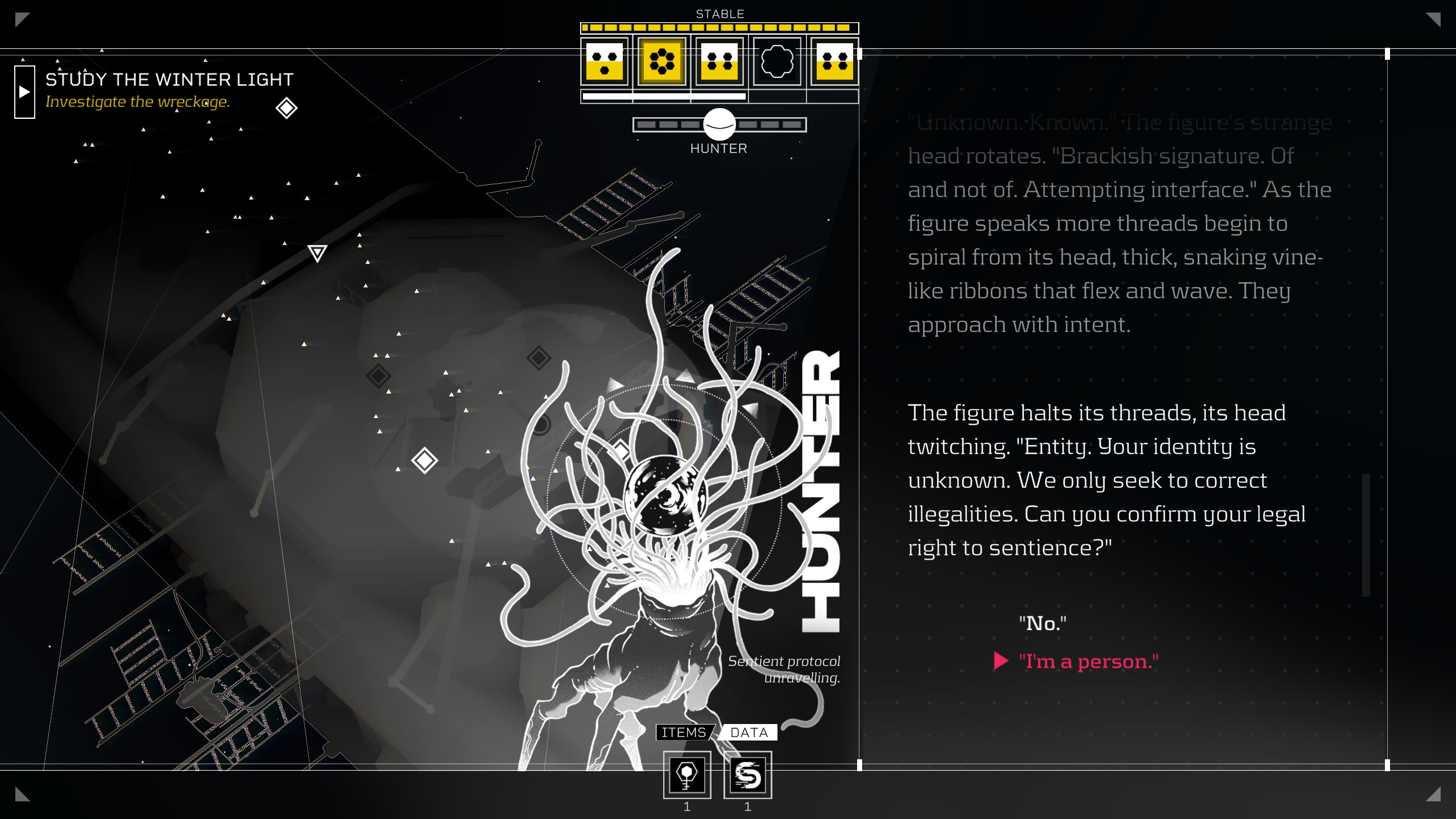

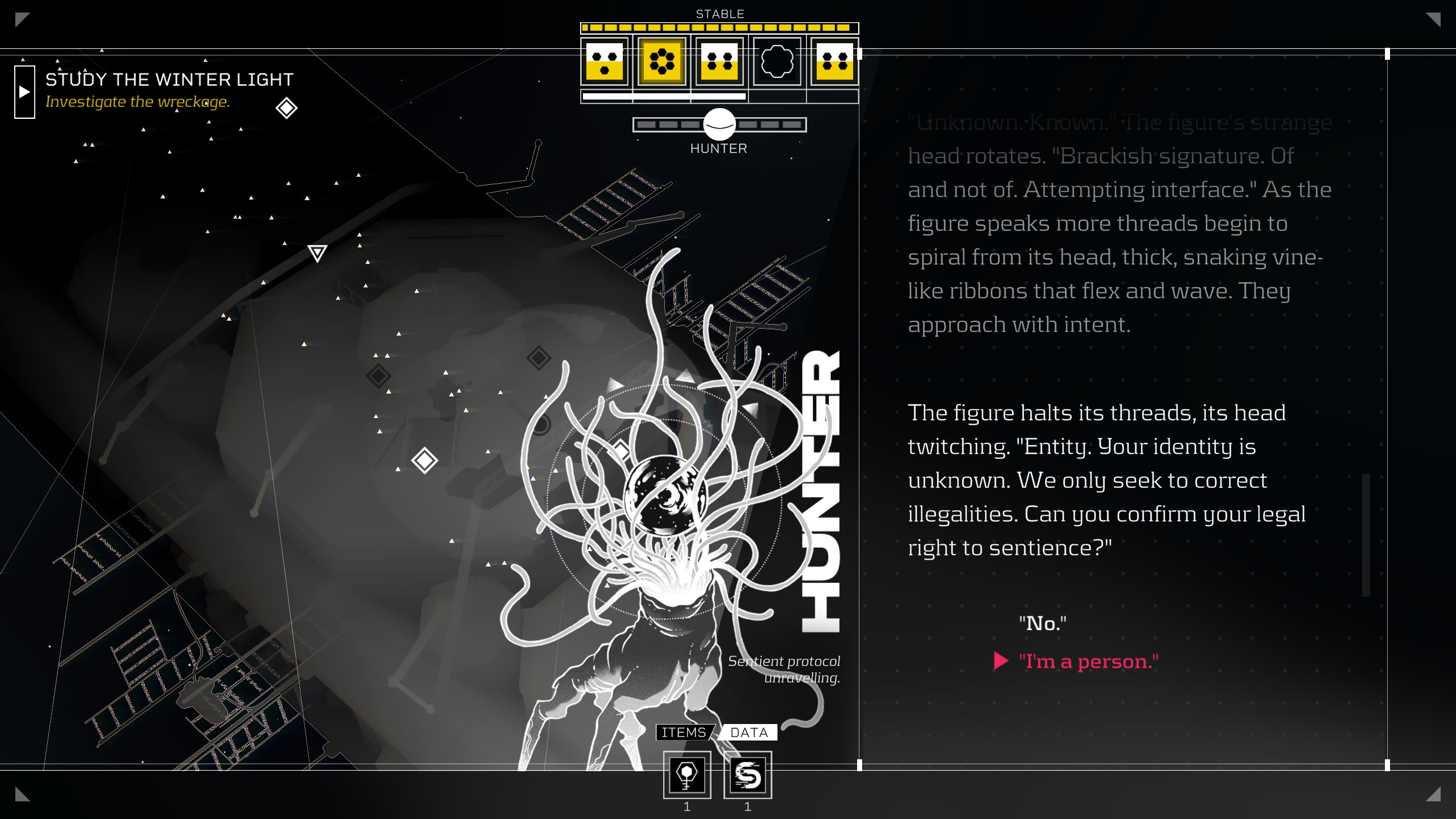

Beneath the Overlook bar, you can stumble upon a vending machine, NEOVEND 33, which is displaying signs of sentience. In truth, it's inhabited by an AI which has, in response to its own existential threats, disconnected from the digital cloud permeating the Eye in order to elude a digital predator. The Sleeper is capable of tapping into that same cyberspace, filled with nodes of encrypted data, information about each of the factions on the station. This hacking layer is a useful design element — each node only accepts a single die value (usually in the lower half of the range) as a cost to decrypt the data, giving the player a way to put bad rolls to good use. Data is useful as a trading good in some instances, either directly for cryo or something else harder to get your hands on, so soon enough you’ll have your hands on a fair amount of it.

By this point, you’ll have noticed that, as you decrypt these nodes, another clock is ticking upwards. The game doesn’t take pains to alert you to this at first, but each time you perform a hack, an ancient artificial intelligence lurking in the cloud grows closer and closer to discovering you. Hunter — the creature that Navigator has been hiding from — stalks cyberspace searching for sentient beings to report to its counterpart, Killer. Soon enough, it senses you, and Navigator, too, once you’ve brought them back online.

Cyberspace is less like a material thing in Citizen Sleeper than it is a metaphysical realm, but one with an ecosystem as wild and eerie and dangerous as any in our world. In contrast with the social realism of the rest of the game, this space has a spiritual quality to it; here, the Sleeper discovers the true nature of this inhuman part of themselves, the aspect of their duality that has been the cause of a good deal of anguish on the other side. There’s something peaceful and ethereal in the idea that the Sleeper could relinquish their mortal coil and inhabit this new form in cyberspace, and it’s an idea that becomes very tempting once Hunter and Killer are dealt with.

Each of Citizen Sleeper’s endings is made available by bringing two completely separate storylines to their conclusions. It’s a simple design paradigm, but in each instance, the crossing of threads is wonderfully surprising and yet perfectly apt. The effect is, I think, magic.

Before I reached the end game, I had an idea of what the game’s endings were going to be “about” in the big picture — the dramatic question in each would be whether the player left the Eye for a chance at another life, or stayed in the flawed but caring present. Sometimes, you can see the choice coming from a mile away: Lem and the Sleeper meet on the job site as they construct a ship destined for another planet. There are some complications on the way, but of course you’re going to be given the option to join him and Mina on the journey. Other times, a character you had written off completely returns out of the blue and offers you an escape (I won’t even allude to what this scenario is — it’s the one that really left me stunned).

As a consequence of this design, you can reach the endings in any order. It’ll depend on whose stories you find most compelling, or maybe just whose you find first — the pacing of how you encounter the ending-critical storylines can, in truth, be a bit lopsided. By the time I reached my third and final ending, though, I knew what was coming.

Riko is a botanist you meet in the Greenway, the overgrown stretch of station that’s at the furthest reaches of the ship from where you begin. The Greenway, of course, is where you’re finally able to cultivate the mushrooms Emphis is looking for, but Riko is also preoccupied with the new growths in the Greenway since Solheim’s departure from the Eye.

You see, the whole situation in the Greenway is inexplicable using the scientific and analytical frameworks that Riko has cultivated over time. She suspects you can help her find answers, and so tasks you with growing particular mushrooms and exploring cyberspace until she realizes the connection — the Sleeper is calling forth the influence of digital beings into the material world, causing changes in the biological make-up of certain fungi such that they can be used to synthesize more stabilizer, the substance the Sleeper needs in order to continue to live outside Essen-Arp’s grasp.

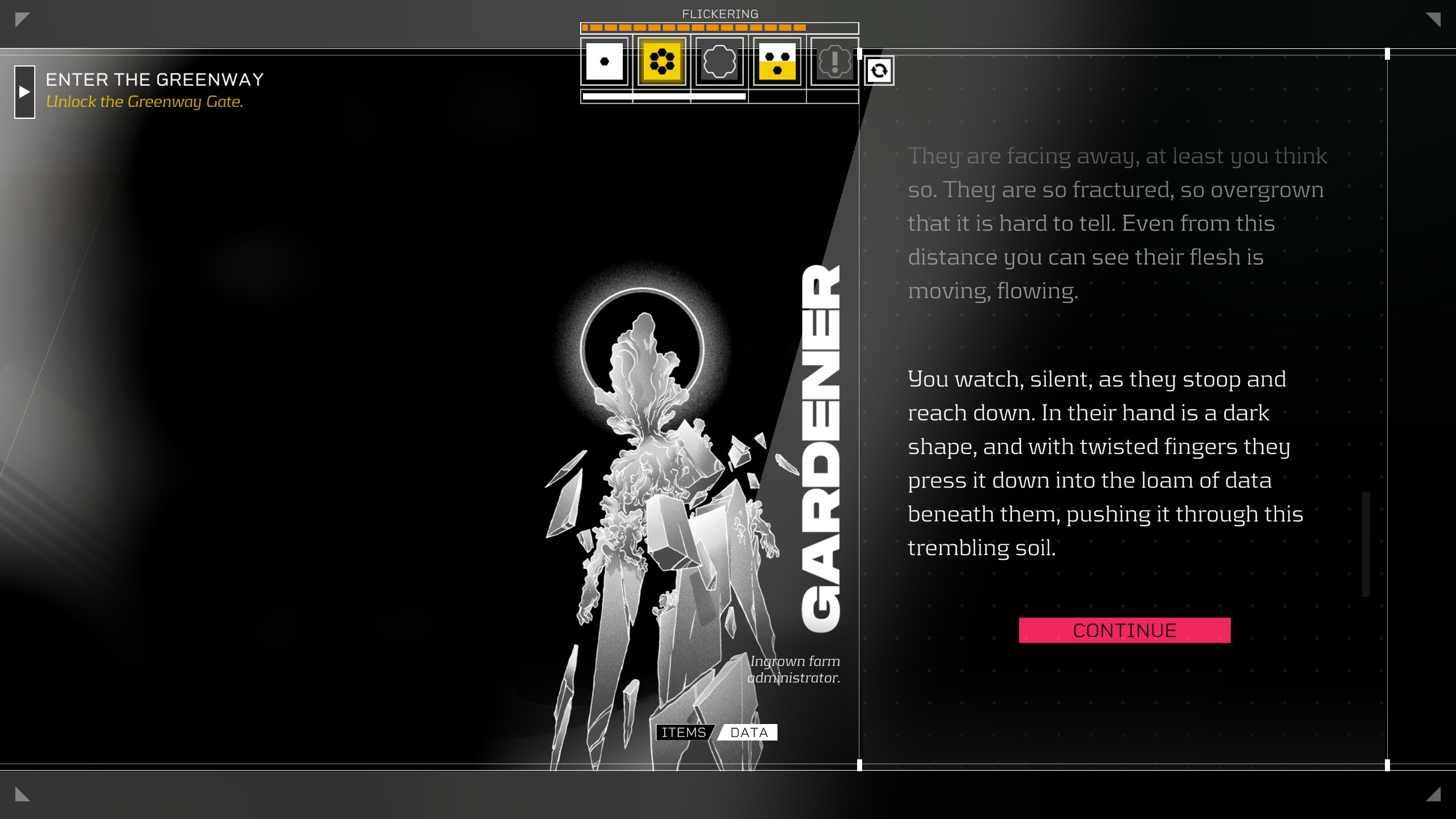

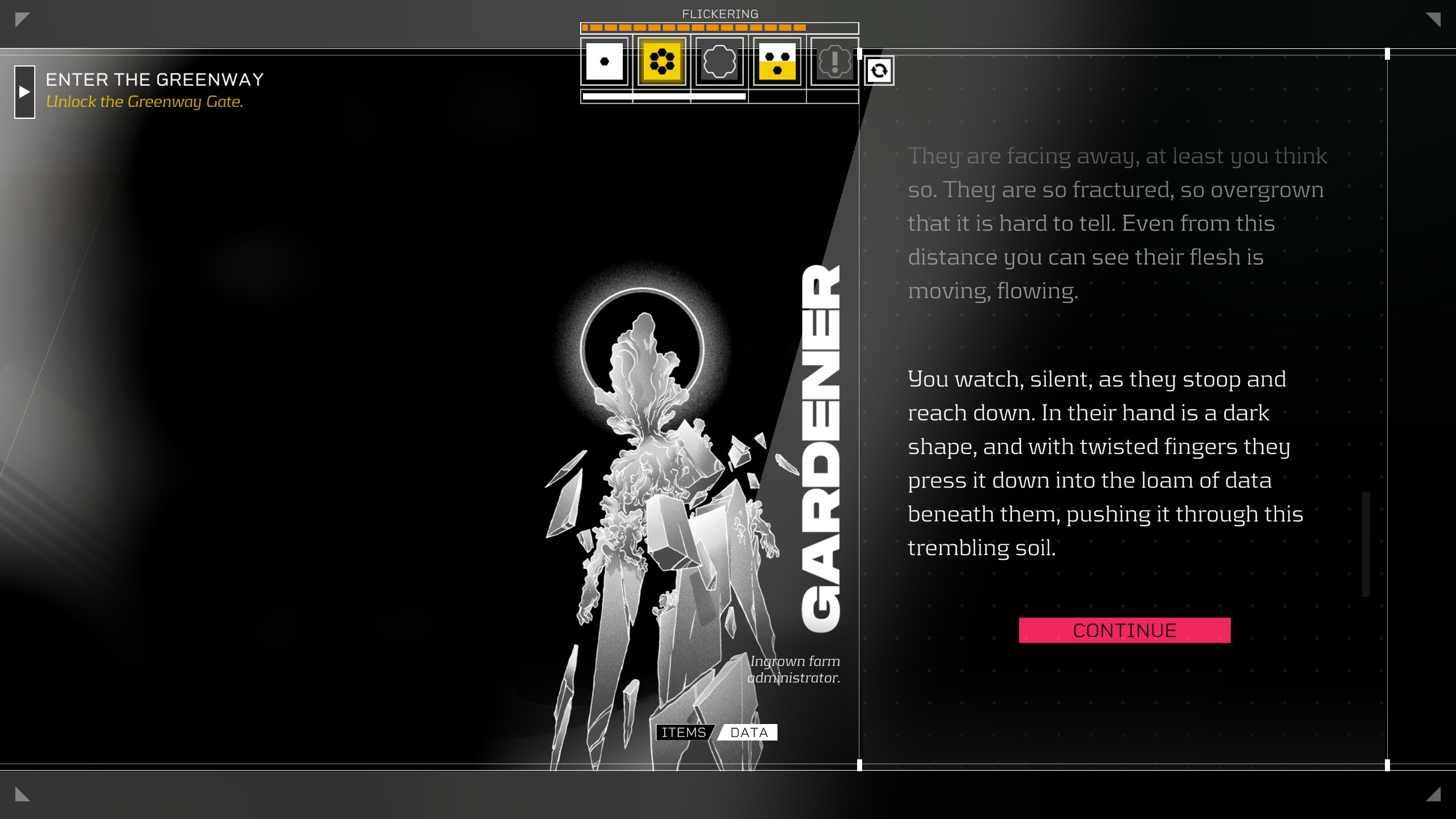

A final gift from the other side is presented, a sort of crown-seed which Riko helps you use to dive into the depths of the station’s digital realm in order to commune with the oldest being aboard: the Gardener. The Gardener offers the Sleeper the same choice as is presented in all the other endings: cut the threads tying you to the world as you know it — the Eye, the Greenway, the Lowend, Emphis, Lem, Mina, Riko, your decaying body, the grief and the pain and the precarity — or stay there.

I made the same choice in all three endings, in effect. No offer to leave the Eye was tempting enough for me to give up what I had built there. There was, of course, some heartache and regret — the moment Mina realizes you’re not going with her and Lem just kills me — but largely, I found the decision pretty easy to make, and once I’d made it once, inertia meant it was even easier to make it again.

The Gardener’s offer was the most tempting, though. I still find myself wondering occasionally what that version of the Sleeper’s life looks like, what kind of language would be used to evoke that radically new existence.

But, as I’ve said, I chose to remain on the Eye, with the people I had met and helped, and who had helped me. In some ways, making that choice three times rather than just once affirms it even more strongly for me. In the moment where you return from your audience with the Gardener, following the threads back to the ordinary world, you wake beside Riko and feel the warmth of her hand as it grasps yours. She admits to you that, while you were under, she came to realize you might not come back — that this friendship she had fostered with you would end abruptly, even as she sat there holding your hand, confirming your physical presence. I can't always recall the exact words my Sleeper exchanged with her in this moment, but the genuine warmth they expressed will never leave me.

Spoilers are over now. You’re safe. Sorry about that.

Earlier, I mentioned that I think Citizen Sleeper provides a great blueprint for other scope-conscious narrative games, especially ones that want to emulate its tense systems and player-directed narrative design. The primary evidence I have to back this claim up is personal — the game swiftly inspired me to take up a side project making a game very much like it with some good friends of mine. But it’s also evidently been a success for the developer, and I don’t just mean critically and commercially: in an interview published just after the game’s second free content update, Episode: REFUGE, Damian Martin talks about how the tools developed for the game, as well as its core design, were influenced by a desire to make creating and adding content to the game as simple as possible. The three new story drops were planned to take a month of development time each, and while they’re not rivaling the main game in terms of length, the speed with which they’re being deployed to the game is impressive.

I don’t mean to suggest no other game has done what Citizen Sleeper has in regards to a mix of authored narrative and systems in between, or even designing the game and its tools with an eye towards easily adding new content, but it's hard to deny that this particular synthesis of such a sticky game loop, the tabletop-influenced mechanics, and grounded stories with this much character and feeling makes all those additions feel welcome and vital. Citizen Sleeper offers a tremendous example of how a compelling (though not always perfect) game loop can electrify even a primarily narrative-driven game.

.